Why Courage Can Feel Impossible

How an outdated definition of courage is costing us more than we realize

read time: 5 minutes

One of the most unexpected things I encountered when I told people I was leaving my corporate career was how many people said they’d always thought I would do this. Two people, in particular, told me they were surprised I hadn’t done it already. I got curious. What was so obvious to them that wasn’t to me?

Some of my mentors used the word courage. I’ll tell you this: I didn’t feel courageous for a second. Most of what I was doing felt like every problem I’d solved before: look at the variables, gather data, scenario plan, figure out the right fit, then act. That disconnect between how courage looks from the outside and how it feels from the inside is what got me curious.

What does courage actually feel like?

What I found had been hiding in plain sight. Yet another inherited belief.

The Inherited Belief

One of the earliest documented definitions of courage comes from Ancient Greece. In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle describes who is brave:

The man who faces and fears the right things, with the right aim, in the right way and at the right time is brave. (…) Properly, then, he will be called brave who is fearless in face of a noble death.

In it, he argues the highest form of courage was found in battle. Soldiers willing to sacrifice their lives protecting their city-state.

That image—brave heroic acts, self-sacrifice for a greater cause—is the one most of us still carry. It carried on through Romans and Christianity and is still reinforced today through films, books and medals.

That was thousands of years ago.

Today, we have a gap.

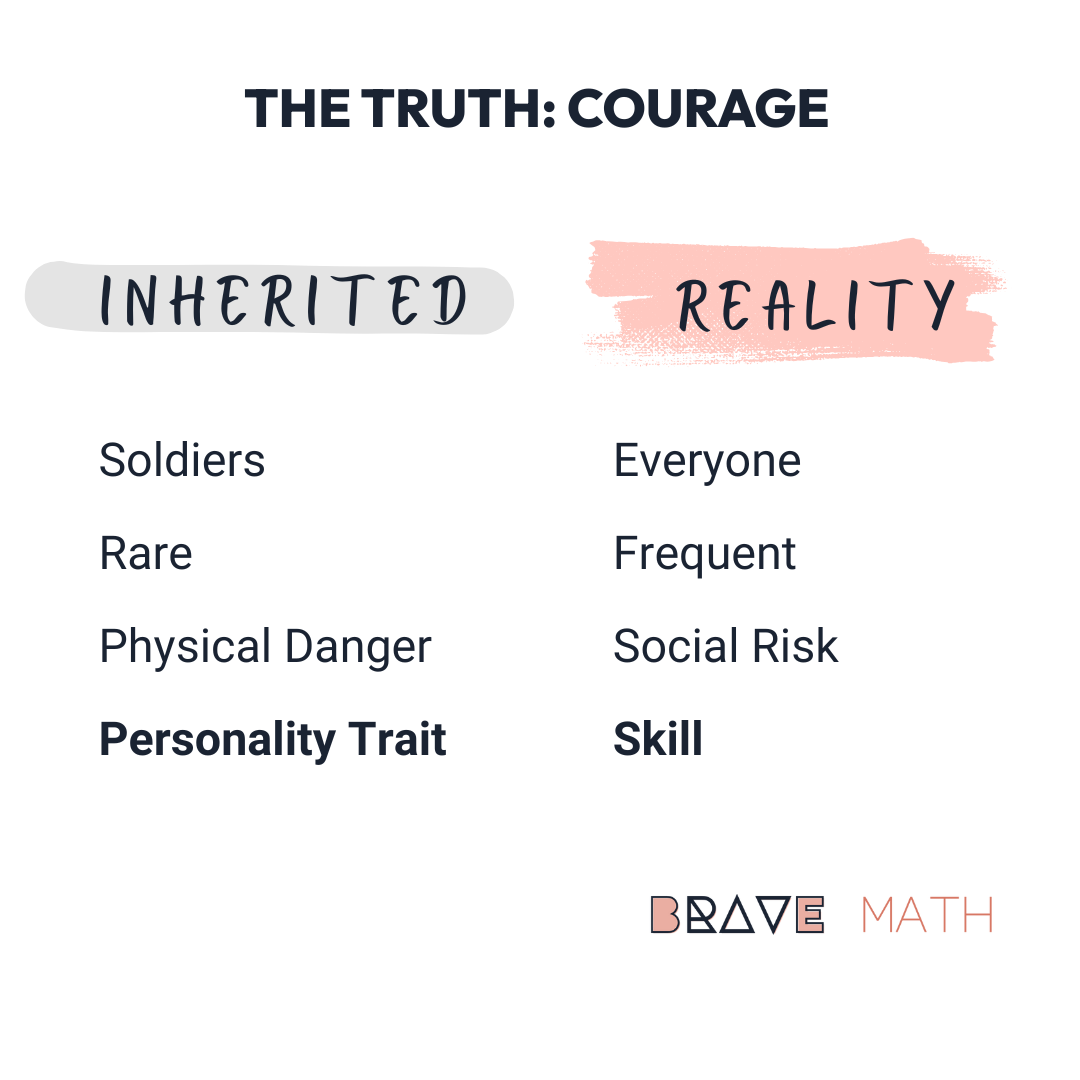

The Courage Gap

Let me show you something…

What image comes to mind when you think of courage?

It probably looks something like this:

Now consider these situations:

A child who stands up to a bully

A person who voices an unpopular opinion in a meeting

Someone who leaves a group that repeatedly disrespects their boundaries

Are these courageous acts? I imagine you would say yes.

But did they come to mind when I asked you to think of courage? Probably not.

This is a problem:

Our mental model of courage highlights rare, dramatic moments and pushes to the fringe the kinds of courage we actually face most often. It ties courage to the extraordinary, when most of us need it in ordinary, day-to-day moments.

That gap makes courage feel bigger and harder than it needs to be. And when courage looks that distant, it’s no wonder many people think it’s outside their reach. This model doesn’t help us act when it matters.

Science Tells Us the Truth

Once I looked past the motivational posters, I found substantial data on courage that rarely breaks through.

Three findings stood out to me.

1. Thinking you’re brave isn’t what makes you act brave.

When psychologists studied what actually predicts courageous action, they found that seeing yourself as a courageous person wasn’t very helpful. What mattered instead was something much more tangible: the decision you make when fear is right in front of you.

In these studies, people were asked to face something they were genuinely afraid of. When they described themselves as courageous weeks earlier, it didn’t predict what they did. But when they paused just before the moment and decided whether they were willing to move forward despite fear, that choice predicted their behavior almost exactly.

Courage showed up not as an identity, but as a decision.

When I left my job, I didn’t feel courageous. I felt scared. But I’d made a calculation that said: leave. So I did. My goal mattered more than how I felt. The same can be true for you. You don’t have to see yourself as brave to still behave courageously in an important moment.

2. Courage can be trained.

There are certain people—mostly nurses and the military—who are already being trained in courageous action. Multiple studies show training increases courageous behavior, treating courage like a skill you can strengthen. If they can learn it, so can we.

3. Fear is not the problem.

One study I found particularly insightful comes from research on paratrooper trainees. Those defined as courageous showed just as much fear (physiological arousal) before a jump as those defined as fearful. The difference wasn’t the fear. It was the action.

The science was confirming what I’d seen: Courage isn’t a feeling you wait to have. It’s a calculation you learn to make.

The Modern Challenge

This matters because the dangers we face in 2025 are increasingly social, not physical.

We’ve all felt that fear. Setting a boundary with a parent. Speaking up in a meeting when our perspective contradicts our manager’s. Leaving a job that pays well but silently takes away our health. Asking for what we need in a relationship.

These aren’t life-or-death situations, and for a long time I minimized that fear. I was surprised to find that our brains actually register social threats in ways remarkably similar to physical injury. Studies on social pain demonstrated that rejection, exclusion, and disconnection activate the same neural pathways as physical pain.

Our brain doesn’t distinguish social vs physical threats as clearly as we might think.

So when you feel afraid to have a difficult conversation, that fear is responding to real risk. Just because you’re not on a battlefield doesn’t mean courage isn’t required.

Here’s the silver lining:

Social risks are risks you can anticipate.

Which means they’re risks you can prepare for.

Why It Matters

The research on courage’s benefits deserves more attention. I experienced many of these in the last year but never connected them explicitly to courage.

People who act courageously have lower anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms. They report less fatigue, less chronic pain, and better physical health.

And here’s the finding that can help us during periods of transition: on days people choose to act with courage, they feel better and less stressed—even after dealing with the discomfort of the feared action itself. Not eventually. The same day.

What Comes Next

Courage can be cultivated. Science confirms it. My experience says it’s essential.

For now, identify one decision you’ve been avoiding.

Not the Braveheart kind. Something specific.

If you’re willing, reply and tell me what it is. I’m curious where courage (or avoidance) is showing up for you right now.

PS: For me, this past year was a year of clearing: divorce, career, housing, health. This next year is my year of rebuilding. The courage I’m focusing on now is doing it with intention toward what matters.

Sources:

The Role of Courage on Behavioral Approach in a Fear-Eliciting Situation

Exploring the foundations and influences of nurses’ moral courage

Does Rejection Hurt? An fMRI Study of Social Exclusion

The effect of courage on stress

Handbook of Self-Regulation

Exploring the foundations and influences of nurses’ moral courage

Does Rejection Hurt? An fMRI Study of Social Exclusion

The effect of courage on stress

Handbook of Self-Regulation